Duolingo was made with a mission – to make free education and increase income potential through language learning. However, the same mission that has helped it grow to a business valued at $2.4 billion with over 500 million registered learners, has led to tensions that continue to define the business.

How a startup can survive without charging its users? How to design a startup that isn’t too hard to lose people, but isn’t too easy to compromise education? And how to balance monetization goals while also keeping education a free product?

How a bot-fighting test turned into edtech’s most iconic brand, Duolingo

Luis von Ahn is an entrepreneur who has dedicated his career to scaling free education. His work includes building the technology that would become CAPTCHA, those human-annoying but bot-preventing little tests that pop up when registering or logging in to popular internet services like email.

An undergrad from Duke, von Ahn went for a computer science Ph.D. at a top-ranked Carnegie Mellon University. That’s when he attended a talk by Yahoo’s chief scientist about 10 of Yahoo’s biggest headaches. One issue stood out: hackers were creating bots that register thousands of email addresses to send spam.

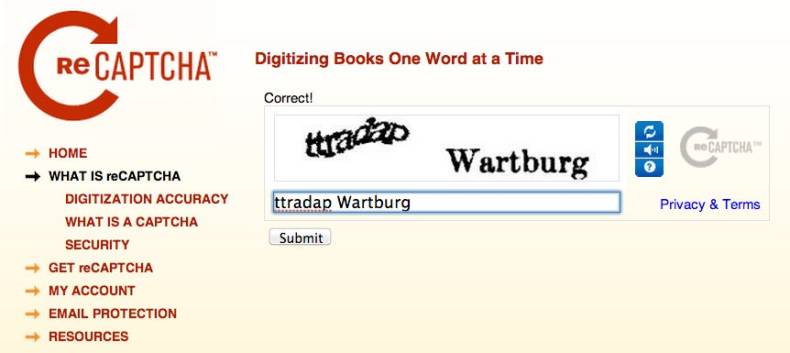

Inspired, von Ahn and a team led by his then-adviser Manuel Blum created a nifty little test that could distinguish between bots and humans. The test, called a CAPTCHA, presented squiggly, ink-blotted words whenever a user tried to log in. Computer vision at the time couldn’t read the obscured text, but humans easily could, creating a useful signal. He gave it to Yahoo for free.

In 2005, he launched reCAPTCHA. These new tests would have the same goal as CAPTCHA, but with a twist: the prompts would all be scans of books. Users would complete the security test while also helping to digitize books for the Internet Archive.

The product-led growth behind edtech’s most downloaded app

The gaming world was rapidly innovating around him in the mid-2010s. Games on mobile, and video games generally were getting more engaging, with in-app currencies, progress bars, and an experience that felt creatively addictive. He suddenly saw connections between the entertainment that games provided and the patient learning required for languages.

“Wouldn’t it be cool if the skill got harder and harder, kind of like how a character in a game gets more powerful and powerful?”

Every game needs some form of experience points and leveling up, and for Duolingo learners, that progress comes in the form of skill trees. These trees, which were conceived by a design agency during the company’s early development, are Duolingo’s core experience, a visual representation of language skills that are interconnected and get progressively more difficult and refined over time. Each skill is a prerequisite for another. Sometimes it’s just logic: in order to be able to speak about restaurants, you probably should be able to introduce yourself first.

The growth power of a cartoon owl meme

Duolingo had its “leveling up” model figured out, but now it had to integrate gamification into every nook and cranny of its app. One of its first challenges was rebuilding the sort of teacher-student emotional bond that can help students stay motivated to learn. No one likes to fail, and Duolingo stumbled upon a scalable approach through its cartoon owl mascot Duo, also thought of by the design agency behind the skill trees.

Whenever users succeed or fail at their lessons today, they are likely to be encouraged or admonished by Duo’s presence. Designers sprinkled Duo throughout the product, looking at Super Mario Brothers as an example of how to use iconic art to create a friendly gaming experience. In early iterations of the app, Duo was present but static, more of an icon than a personality. That changed as the company increasingly pushed harder on engagement.

How Duolingo became fluent in monetization

Duolingo launched saying it would never do advertisements, subscriptions, or in-app purchases. All these approaches now exist on the platform. Today, Duolingo has a simple freemium business model that is remarkably unconventional. It has a free version with all of its learning content, and it charges a subscription of $6.99 per month for paywalled features such as unlimited hearts, no advertisements, and progress tracking

While the company’s investors were relatively lenient in the early years, patience was starting to run thin. In June 2015, Duolingo raised a $45 million Series D round led by Laela Sturdy of Google Capital (later rebranded CapitalG), valuing the company at $470 million. She invested because of Duolingo’s growth and engagement numbers but confronted von Ahn with some direct advice.

“She said to me, ‘Look, it worked for you to continue getting bigger and bigger checks from venture capital,’” von Ahn said. “‘But this is the last time it works for you … if you’re trying to con people, you cannot con anybody bigger than us [at Google].’” Duolingo’s valuation wouldn’t just be at stake next time it went fundraising on Sand Hill Road, its’ very survival would be as well.

Looking back, Sturdy said that she always “had confidence that they would come up with a revenue model” because of Duolingo’s passionate and organic users.

Von Ahn says his conversation with Sturdy is what really changed his mindset about money. After the Google check hit Duolingo’s bank account, he and Hacker began thinking about ways to make Duolingo as much a monetary success as it had been an educational one.

Duolingo can’t teach you how to speak a language, but now it wants to try

“I won’t say that with Duolingo, you can start from zero and make your English as good as mine,” he said. “That’s not true. But that’s also not true with learning a language in a university, that’s not true with buying books, that’s not true with any other app.”

While Dubreil doesn’t think Duolingo can teach someone to speak a language, he does think it has taught consistency, a hard nut to crack in edtech. “What Duolingo does is to potentially entice students to do things you cannot pay them enough time to actually do, which is to spend time in that textbook and reinforce vocabulary and the grammar,” he said.

That’s been the key focus for the company since the beginning. “I said this when we started Duolingo and I still really strongly believe it: The hardest thing about learning a language is staying motivated,” von Ahn said, comparing it to how people approach to exercise: it’s hard to stay motivated, but a little motion a day goes a long way.

Duolingo helps people get motivated to learn a language, even if it’s just five minutes

Duolingo co-founder and CEO Luis von Ahn compare his company to the elliptical. On the efficacy of Duolingo, and the long-standing critique that it still can’t teach a user how to speak a language fluently.

“Now, there’s a difference between whether you know you’re doing the elliptical or yoga or running, but by far, the most important thing is that you’re doing something [other than] just walking around,” he said.

What von Ahn is getting at is that Duolingo’s biggest value proposition is that it helps people get motivated to learn a language, even if it’s just five minutes or an elliptical workout, a day. He thinks motivation is harder than learning itself. Do you agree?